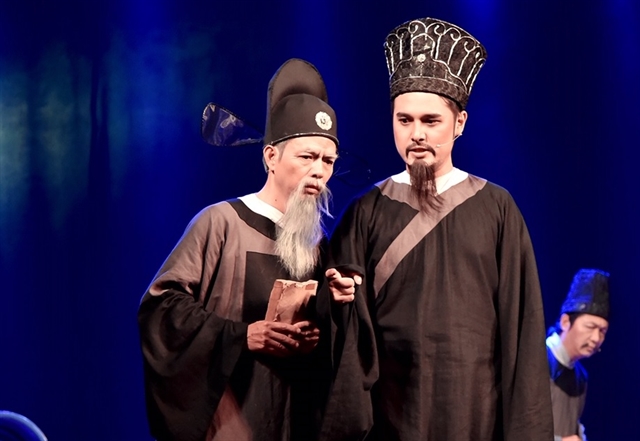

A performance of The Cup of Poison to celebrate the 100th anniversary of local western-style theatrical plays being staged in Việt Nam. Photo courtesy of vietnamplus.vn

by Nguyễn Mỹ Hà

The thousand-year-old culture of Việt Nam is so rich in theatrical tradition – be it plays, comedies, tragedies or musicals – that each region seems to have its own operatic form.

The north has the hugely popular chèo plays performed in village courtyards for the entire public to enjoy. The centre possesses the more sophisticated, in-depth tuồng plays, often taking place in roofed venues and performed for royalty, while the south has the heart-stopping melancholic tunes of cải lương plays and their lengthy lyrics that include up to 99 words in a single breath.

While tuồng (classical drama) and chèo (popular opera) were traditional theatrical plays, cải lương (reformed drama) was a renewed musical style born in the early 20th century by incorporating vọng cổ (nostalgic) melodies into the plot.

Around the same time, a western genre of performing art called kịch nói (straight play), also made its debut in the country. With the premiere of Chén thuốc độc, or 'The Cup of Poison', penned by playwright Vũ Đình Long in 1921, the western-style play – without singing – was born. The genre now celebrates its 100th anniversary in the country.

The beginning

FLOWERY PERFORMANCE: Hoa cúc xanh trong đầm lầy (The Blue Chrysanthemum on the Marshland), one of many theatre hits by scriptwriter Lưu Quang Vũ in the heyday of the 1980s. Photo courtesy of danviet.vn

Theatre critics are agreed that such plays came to Việt Nam with the French long after they invaded the country, at some point during the latter half of the 19th century.

The first French play performed in Hà Nội in Vietnamese language, translated by Nguyễn Văn Vĩnh, premiered in the city's Opera House on April 20, 1920. It was Le Malade Imaginaire (The Imaginary Invalid) by Molière. The Tiến Đức Open Mind Society co-sponsored the première to raise funds for the families of Indochinese soldiers who fought for France in World War I and never came back.

During that time, such plays were only popular among the ruling French and some western-trained local intellectuals, while your average audiences preferred singing in their performances.

One and a half year after the Molière premiere, Vũ Đình Long presented his play Chén thuốc độc (The Cup of Poison) at Hà Nội's Opera House, and more local playwrights began penning their own scripts.

Phong Hóa and Ngày Nay newspapers even ran readers' scripts sent from around the country.

Vũ Đình Long, now known as the father of Vietnamese theatre, made his name in the early years of the 20th century, owning the Tân Dân Publishers and various publications, namely Tiểu thuyết thứ bảy (Saturday Novel), Phổ thông bán nguyệt san (Popular bi-monthly magazine) and Hữu Ích (Useful).

He orchestrated both literary circles and the wider market, and played a major part in the national literary, newspaper and publishing scene of the time.

At 25 years of age, he penned The Cup of Poison and Tòa án lương tâm (The Court of Conscience), ushering in an entirely new genre of performing arts throughout the country.

In a conference on Vũ Đình Long's life and works earlier this month, critic Ngô Tự Lập said that The Cup of Poison had an impressive launch not only thanks to its new format, but for the way it cut into urban family crises, reflecting the larger societal conflicts and issues of the country in the early 20th century. He said that the play also showed its author's in-depth dissection of the tossing and turnings of what were then degrading social norms and values.

Long went on to write other plays reflecting contemporary issues, including Đàn bà mới (New Women) and many more.

Trained in French culture and education, he also translated other world famous plays such as Shakespeare's Hamlet, Corneille's Motherland and Chekhov's Uncle Vanya with the adapted Vietnamese name Uncle Vân.

FATHER OF VIETNAMESE DRAMA: A collection of Vũ Đình Long's works. Photo courtesy of thethaovanhoa.vn

In 1935, poet Thế Lữ, who also wrote some of Việt Nam's best crime and detective novels, founded Thế Lữ Theatre Troupe in Hải Phòng with his friend. It was the first country’s theatrical troupe, tilting toward professionalism.

During the brief period of less than two years when President Hồ Chí Minh declared Việt Nam's independence in 1945 and before they had to retreat to the mountains in the north for a nine-year long war of resistance against the French, theatrical plays flourished in Hà Nội. Small groups between five and 10 people got together to play, and often even bigger groups.

The form was a useful way to communicate to the wider public, with plays written to commemorate heroic ancestors and call on the masses to rise up against the French colonialists.

Clear prose that was sharp and easy to grasp was a popular quality of theatrical plays, and even inspired the common people to go to evening classes to learn to read and write to reduce the illiteracy rate and encourage economic production.

After the Hồ Chí Minh Government had to evacuate to the mountains, back in the cities of Hà Nội and Sài Gòn, western plays came back to the stage with plays of Molière, Shakespeare, and others focusing on the history of the Orient and Việt Nam.

Theatrical plays became a subject taught at the Sài Gòn National Academy for Music and Drama. Kim Cương, a cải lương star, and successor of a Nguyễn King also made her name playing in these dramas without singing.

During the time when the country was divided in two, plays also saw triumphant growth in the North, with schools shows and students taking part across the board.

Language students even staged plays in French and Russian. The best theatre actors and actresses were treated like rock stars.

The stars

PLAY TIME: Dưới cát là nước (Water Runs Underneath Sand) by scriptwriter Nguyễn Quang Vinh puts love and hatred under detailed scrutiny. Photo vov.vn

Prior to the new reforms and radical thinking in 1986, the way the country was run economically was inefficient and theatres could not afford to keep staff fully paid. But the Government soon eased its controls, allowing private troupes to stage public performances.

New scripts were blooming with names such as Thế Ngữ, Doãn Hoàng Giang and Lưu Quang Vũ, who all wrote about the pains and joys of Vietnamese society, gradually replacing theatrical productions of political contents.

Vũ, the most successful playwright of that brief bloom, penned scripts to full houses from north to south. Scouts from theatre troupes came to his home in Hà Nội waiting to fetch the latest play exclusively for their theatres.

Many stars were born from those days becoming pivotal artists with superb skill. People's artists Hoàng Cúc and Trần Vân, Hoàng Dũng and Lê Khanh were a few of Vũ's artistic disciples.

But this renaissance did not last long. In 1988, a car crash killed Vũ, his wife and their youngest son. In 2000, he was posthumously awarded the Hồ Chí Minh Prize for his play Lời Thề Thứ Chín (The Ninth Pledge).

The free fall

COURTROOM DRAMA: A Court Case: God's Uncle by writer Lê Chí Trung, directed by People's Artist Ngọc Giàu, a new work from HCM City College for Theatre and Cinema. Photo courtesy of thanhtra.com.vn

Though the Vietnamese economy has flourished since 1986, the theatrical scene has not much improved since, with people increasingly turning to forms of mass entertainment such as video tapes, DVDs and, today, online streaming. Most theatrical entertainment is watched on screens in the home.

The number of people frequenting cinemas, or theatres has decreased sharply since 2000. Artists have to work odd jobs to make ends meet and theatre group managers struggle to tickle audiences and lure them to the theatre.

For many years, tragedies would not win spectator's hearts. Everyone had to turn to comedies, or battled to find themes that appealed to viewers.

The National Theatre of Việt Nam, and the Hà Nội Youth Theatre have tried to stay faithful to their successful repertoire. In the south, French centre IDECAF hall, and Hồng Vân's Small Theatre often stage comedies.

Today, television series can get the best actors and actresses known nationwide, faster than decades-long theatre roles on the stages of Hà Nội and beyond.

But it is a problem worldwide.

Leon Quang Lê, a Vietnamese artist who performs in Broadway musicals told Việt Nam News that it was a job of constant discrimination and struggle.

He left Broadway to spend a few years making a widescreen movie, Song Lang, on the art of cải lương, which received acclaimed reviews from critics, but was a commercial failure.

The curtain call

THEATRE DYNASTY: 'The Architect Vũ Như Tô' by writer Nguyễn Huy Tưởng looks at the turbulent society of the Lê Dynasty. Photo danviet.vn

On October 21, the play to start it all, The Cup of Poison opened at a week-long festival in Hà Nội Opera House, abridged slightly to be shorter than the 3-hour original. Director Bùi Như Lai recreated the life of four people in a family 100 years ago, reflecting not only their life crises, but also those of wider society at large.

It shows the free fall of a wealthy family after the father dies leaving them a fortune. A superstitious mother spends money going from temple to temple praying for the family's well-being with a supporting daughter-in-law. An elderly son has a well-paid job but overspends his high salary and squanders the family fortune on alcohol, music and women (some things never change). A younger sister loses faith upon seeing everyone else in decline, withdrawing to have an affair with a married man. It all reaches a nadir when a court orders their house to be confiscated.

The titular cup of poison is something much of the family fight to drink in quiet desperation to end their troubled lives, before a family friend reminds them that suicide is the easy way out but it's more difficult to live and win back tattered reputations (such psychological counselling is all well and good, but perhaps it is easier said than done).

Though the play was the country’s first spoken drama, as opposed to the more popular song-and-dialogues performances, director Lai added văn (ritual) singing to his production, making it both visually appealing and adding some hair-raising theatrics from the voices of the singers. The decision to add singing to the play was unorthodox but added considerable colour to the performance.

Văn singing was banned for a long time because it was seen as superstitious, and ceremonies cost so much money they could break the fortunes of wealthy families (perhaps a fitting addition considering the play’s context).

The play was a stunning way to kick-off modern drama in the nation, and it feels as fresh today as it must have back then.

Plays are a wonderful way to combine an artistic vision, while presenting contemporary issues and capturing audience attention, and it is hoped that after a century of performances they will still be able to flourish.

"Over its 100-year co-existence with other traditional theatrical genres, spoken plays can reflect the ongoing reality in the country's life faster, sharper and more truthfully," said Deputy Minister of Culture, Sport and Tourism Tạ Quang Đông at the opening ceremony of The Cup of Poison.

Though a century of western theatre is something to celebrate, there is no doubt that COVID-19 has also been a cup of poison the industry has had to drink, and the jury is still out as to whether it can survive.

As the President of Việt Nam Theatre Association Trịnh Thúy Mùi said at the opening ceremony: “Where it will steer the 100-year-old performing art genre is a question we all have to look for an answer to.” VNS

OVietnam