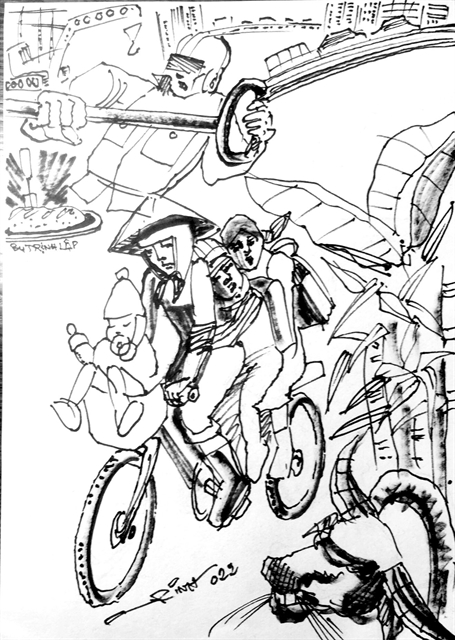

Illustration by Trịnh Lập

by Nguyễn Mỹ Hà

This year Việt Nam looks back at its 40-year-old policy to send workers overseas, though the number of people sent abroad is at a record low due to the pandemic.

The good intention to open doors to the job market overseas sent hundreds of thousands of people to work in eastern Europe between 1980 and 1990. A government resolution cited that "with labour cooperation, we can give jobs and train a group of young people, whom local enterprises cannot take."

From only four countries back in 1980 -- the Soviet Union, East Germany, Bulgaria and Czechoslovakia -- the list has been expanded to more than 40 countries and territories, and more than 30 fields of interest, according to the Ministry of Labour, War Invalids and Social Affairs.

The first 10 years of this wave in the 1980s saw families of guest labourers gaining significant raises in their incomes. During this period, more than 300,000 people went to Eastern Europe, worked and sent their earnings home, estimated at VNĐ800 billion (US$33 million). The workers were not trained, as they were supposed to learn a job abroad and then return home using their new skills to make a living.

The annual remittance sent home by the labour export has now reached between $3 and 4 billion, a remarkable rise over 40 years.

Guest labourers were first trained to work in textile factories and as construction workers. Today, the guest workers work as seamen on South Korean ships, interns in industry, or nurses in elderly homes.

The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the subsequent break-up of the Soviet Union in 1991 ended the flow of guest workers to the Eastern European market. Many workers in then East Germany received a repatriation sum to go back to Việt Nam, but many others opted to stay in the respective countries they had settled in.

Their lives were jeopardised as they faced the harsh reality of social collapse, trying their utmost to stay on and integrate into local societies without adequate language abilities or proper skills to work in companies was tough.

Even local workers suffered. Vietnamese overseas workers went through even worse circumstances, such as marginalisation and police raids.

There has been limited yet profound literature written on the subject. Việt Nam National Television even sent a crew to Russia a few years ago to shoot a TV series about the lives of the Vietnamese expats who decided to stay.

A series of social issues also raised concerns over their lives abroad, though they sent home money to build houses and buy motor vehicles and up-to-date home appliances so their families in Việt Nam could live better.

Sweat, tears, and sometimes even blood were shed to earn money the hard way.

Initially, the workers were singletons, demobbed soldiers, redundant workers or students of vocational schools who had not found jobs. Later, breadwinners of young families also joined the group heading overseas.

This often led to broken families, children growing up with one parent they met once or twice a year, family connections loosened, and children growing up on the finances of a distant parent, yet resenting them for lack of their presence in their lives.

Every year, the number of overseas workers accounts for 7 and 9 per cent of total jobs, helping lift the pressure on employment at home.

But the downside of this life is that when they return home, they often cannot get a job. Some built big homes from the money they made during their working years abroad, but after that they went back to being unemployed because of a lack of skills.

Among the countries and territories that receive workers today are Japan and South Korea, and many Vietnamese workers stay on as illegal immigrants in those countries. To date, eight districts of four provinces cannot send any more workers because of the runaways.

Due to thousands of illegal overstays, Taiwan and South Korea have limited taking on more workers.

Some top officials have called on educating the returning guest workers: skilled workers need a strategic path to get in the picture, and manual labourers need to be trained again.

The social impact of returning workers must be taken into account, with policies rolled out to help them.

The initial issue of training and educating workers has not been solved, and they are still left with unemployment back in Việt Nam, with no skills learned or improved during their working time overseas. And families suffer emotionally as they are scattered in at least two places.

Last week, I took my child's friend home with us as her parents could not fetch her from a birthday party

"My mum has to take care of my two younger siblings. My dad works in Africa, but we speak to him every day on the phone," the child said.

Another family is split apart. Nevertheless, it is good the mother tries her best to give her child everything she would have had if the father had still been at home. VNS

OVietnam