LIBERATED: Phnom Penh on January 7, 1979. VNA/VNS Photo Lê Cương

by Trần Mai Hưởng*

The next morning, we left Hồ Chí Minh City late. The maintenance of the Jeep was slower than expected, but it was necessary in preparation for the days to come. We drove at top speed to get back to the frontline. Again, we drove through Tây Ninh, Svay Rieng and Pray Vieng. As we approached Neak Loeung Ferry, I started to see deserted streets. I had the feeling that the frontline had moved forward. The war development was too fast. The crowded military posts on previous mornings were now empty. I urged Thu to drive faster. The road was bad so we arrived in Neak Loeung Ferry in the early hours of the afternoon. Many units were queuing to board the ferry. In my queries, I came to know that the Pol Pot forces retreated from its defence line last night.

Thanks to the military mobile ferry moved up from the south, many units were able to cross the river in late morning to advance straight into Phnom Penh. We were like sitting on fire. On the other bank of the river, gunshots could still be heard, but at a lesser level. I searched for the incharge of the ferry to tell him that we were on a special mission. Meanwhile, Cương and Thu managed to secure some rice and soup from the advancing soldiers. At the order to board the ferry, the soldiers gave us their rice and soup pots to leave. We hurriedly gasped down some rice before getting in the Jeep to move down to the ferry. We would wait to continue the rushed meal on the ferry, there was no other way.

The whole unit moved forward. We could not find our Political Commission to join its formation but had to go ahead on our own to Phnom Penh. There might be risks but that was the only way to get to the city as soon as possible. Cương and Thu promptly agreed with me. My heart nearly stopped when the Jeep seemed unable to get on board the ferry because its ground clearance was too low and the pathway was bad. Yet everything was alright in the end. As we moved up to the bank, we followed National Road 1 behind a giant GMC army vehicle. The Jeep looked much smaller now. From the road sides, there were still some gunshots here and there. I told Thu: "At all costs, we need to follow the army formation. A step back and we are dead."

PATRIOT: Everyone plays their part in Phnom Penh on January 7, 1979. VNA/VNS Photo Lê Cương

Thu nodded and tried his best to tailgate the giant vehicle in front. Noticing the journalists following, our soldiers waved their hats to encourage. The road into the city was totally new to us. Pol Pot troops were still hanging around. No one would wait for us. As the big vehicle sped up, we found it really hard to follow. The distance expanded. I was sitting in the front seat and could do nothing but encourage Thu to drive carefully. There were no car tracks to keep on and avoid land mines. In fact, we had no time for it either. The point now was how to move on as fast as possible before sundown. We must enter the city before dark. The road was full of new artillery shell craters, making the car bounce. Corpses of civilians and Pol Pot troops from a few days earlier were scattered around, many had started to bloat, releasing the bad smell that made one vomit. We tried to move fast, the faster the safer.

At some point, I felt as though someone was aiming his gun towards me. I thought of my two-year-old son and his innocent face waiting for me every afternoon at his kindergarten. How would my son be if a bullet hit me and I never returned. As a natural reaction, I put my hand on my chest, even knowing that it would not mean anything at this time!

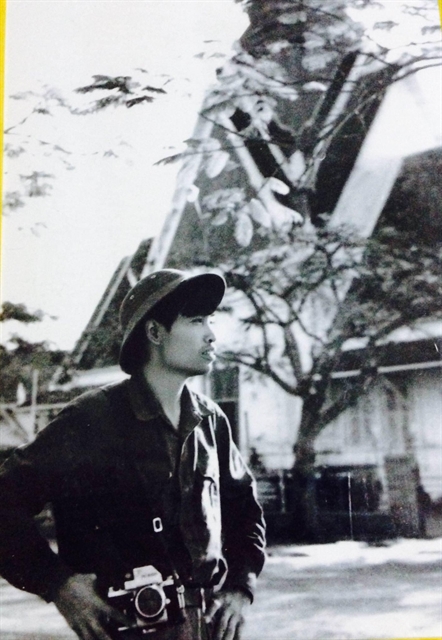

JOURNALIST: Trần Mai Hưởng stands in front of the Royal Palace in Phnom Penh on January 8, 1979. VNA/VNS Photo Lê Cương

At half past twelve on January 7, 1979, the first tank of the Vietnamese volunteer army and Cambodian revolutionary armed forces crossed the Mounivong Bridge from the east and liberated Phnom Penh. Our army units occupied the key positions. The Pol Pot authorities ran away to the west before the arrival of the Vietnamese volunteer army and the Cambodian revolutionary forces.

Unable to contact the Political Commission of the Army Corps, we went to the command of Division 341 asking for shelter. This was also one of the first divisions to enter the city. The division officers, particularly its commander Vũ Cao were eager to help the VNA journalists. At the time, we operated under the common title of SPK (Saporamean Kampuchea or Cambodia News Agency) reporters whose typical outfit included a soft cap that was later called by the people and soldiers as SPK cap.

Thanks to Commander Vũ Cao, we learned of the key developments of the Phnom Penh liberation operation, the essential materials that would be hard to find at that time. Commander Vũ Cao was from North Việt Nam and his family lived in Hà Nội. He also loved and understood the VNA reporters as his son-in-law Đình An was my friend and also a photographer of Việt Nam Pictorial, a publication of VNA. My meeting with him reminded me of my similar meeting with the Political Commissar of Division 304 Trần Bình during the Spring 1975 operation. I was fortunate to have such meetings at the most crucial points of time in my career. Commander Vũ Cao showed his concern by saying: "You could stay here overnight. It is very dangerous to go out because the Pol Pot army remnants are still at large. This evening I will provide you with main information about the situation. Tomorrow morning, someone will take you to some important places in Phnom Penh. I know your job now is very important and should be done quickly.

He really understood our job so we had nothing more to ask for. I only asked him to inform the Army Corps Political Commission and Ba Cúc that we had entered Phnom Penh and were staying at Division 304 and that we would act on our own to be most effective. That night I could not sleep despite all the fatigue after days struggling with Lê Cương and Thu to get through the hardships and dangers.

Worries about tomorrow’s work weighed heavily on my mind. How we would get the necessary information for my articles and return to Hồ Chí Minh City at the quickest pace possible. A strange feeling flooded me. Cương, Thu and I had entered a liberated Phnom Penh, a situation not easy to find in an entire career. I thought of my wife and son, my family and - just like Commissar Trần Bình then - hoping that they knew I was safe and present here. That wish was almost impossible to confirm then. Later, my wife told me that on that evening, from Radio the Voice of Việt Nam, she knew Phnom Penh was liberated. She held my son tight in her arms and cried, making him cry along. She was both joyful and worried, wondering about her husband’s fate.

The next morning, we got up early. Commander Vũ Cao ordered a team of reconnaissance officers to bring us to various places in the city. My first impression was that Phnom Penh was a special city. The curved roofs of the Royal Palace, the Monument of Independence, Mt Penh and the ancient temples all made up a very unique beauty. Yet such beauties were in the midst of this horrifying emptiness and the unimaginable bizarreness of the Pol Pot regime on this land.

I could not believe in my eyes to see an empty and ruined Phnom Penh without any sign of life. All houses were shut down and deserted with no one inside. The streets were also empty. An emptiness that shook every soldier. A dead city in its true meaning. Wild grass covered the gardens. No people, no animals. There was only some Khda flowers showing their reddish petals from the fences, the colour of blood.

VIETNAMESE TEAM: Standing in front of the Royal Palace in Phnom Penh on January 8, 1979. (From left: driver Lê Thu, Batallion No.4 army officer, writer Nguyễn Chí Trung and journalist Trần Mai Hưởng.) VNA/VNS Photo Lê Cương

As we moved on through the streets, we saw all the ghastly details of destruction. The National Bank building was demolished. In the New Market, the stalls had long been vacated, leaving room for damp moss to grow. Schools faced the same fate. The only school open in the city was Tuol Sleng, but it was converted into a prison. When people arrived here, the torture tools and fresh corpses were intact. Major buildings on Mounivong or Norodom boulevards turned into storehouses for necessities for those considered useless. In a small house near the crossroads between Norodom and Mao Tse Tung boulevards, the wall calendar stopped at the tragic day of April 17, 1975 [when the Pol Pot forces took over Phnom Penh]. The same was seen in many other houses. On the floor, a food serving tray was thrown down in rush, now covered with thick dust. Near the Olympic Stadium, the soldiers found in a shop an album, maybe by a foreign photographer, taking shots of the first days of the residents in this city being herded out by the Pol Pot soldiers in black. It was hard to hold one’s tears to see the flocks of people, old and young, women and children in their terrifying look being pushed to the city gates. There were also photos of the city rushing out to the streets to welcome the soldiers in black when they entered the city in the name of 'liberators'. The Tuol Sleng prison still keeps intact its storehouse of torture tools and a room full of human skulls. And there were also a deserted house and a full tray of food from 3 years ago when the people were forced out by the Khmer Rouge troops.

Our Vietnamese army volunteers showed us an album of hundreds of photos capturing images of the people leaving Phnom Penh on that horrible day. Many carried along their small children and elders at gunpoint of the soldiers in black taking the name of 'liberators’. Those faces, in ultimate pain and fear, did not understand why. I supposed that these were the work of a foreign reporter who could not have time to bring them out of the country. Perhaps they could be the work of a Cambodian who left them back. Putting the album into my sack, I knew now I had a precious dossier and asked myself about the fate of this photographer. He or she might well have fallen in the ‘killing fields’ scattered across this country.

That was a society in total hostility with human civilisation. It was clear when one saw television sets, luxurious items and wines piled up in the storehouses. The Khmer Rouge troops piled them up, destroyed them or left to ruin. In another storehouse, there were only shoes for one foot, left or right, and you could hardly find a complete pair.

The reconnaissance team helped us find an army unit of the FUNK in full uniforms, particularly the soft caps. At that point of time, this was a sensitive issue for our photos. The commander was eager to send a full vehicle of soldiers to follow us to the necessary places for photography since we did not have much time.

We moved on to Pochentong Airport. There were only a few aircraft left on the runway. We met writer Nguyễn Chí Trung here. He asked us to take him along as he also wanted to be everywhere in this city before returning back to Hồ Chí Minh City with us. Writer Trung was known to us from very early days when we were still sitting in schools and read his Letter from Mục Village in our textbooks. In real life, he was short with a heavy build, yet quite active, popular and out-going. Sometimes, when I felt annoyed to see the guide team moving too slowly due to other works, he would quickly find a solution and manage everything quite well. We returned to the Royal Palace. The Cambodian soldiers who took over the place quickly led us through the key places and happily helped Cương set up his photos as required. I remembered seeing a silver cup in the middle of the courtyard and showing it to the accompanying Cambodian soldier. He took it on with all respect and said to me that he would hand it over to his superior. On their retreat, the Pol Pot troops took most of the precious items here. The cup might be left out of negligence. Then there was another detail about Nguyễn Chí Trung. As we visited every corner of the Royal Palace and even outside to take pictures, he just sat in one place to take a really good nap! The writer was of a candid type. He might have been exhausted. Meanwhile, the accompanying soldiers kept reminding us to follow suit to avoid possible remnants of the Pol Pot forces there.

We quickly drove to the key places of the city like the Independence Monument, Sihanouk Bridge, Railway Station and Central Market. As we moved along Mounivong Boulevard, we ran into a group of FUNK soldiers who were curiously circling around an old piano. We got out of the car and chatted with them. The company commander, Cay On, was a native of Phnom Penh. He and his family were pushed out of the city on April 17, 1975 and then he lost contact with his family. Later he lived in a farm in the eastern region and joined the revolt against the Pol Pot regime from there. Cay On might be the happiest man in this day of liberation of Phnom Penh. But he was still worried about his parents and siblings, not knowing if they were alive or not. Cay On introduced his friends to us. They were young men and women unable to withstand the Pol Pot regime who had run away to the forests or to take refuge in Việt Nam. Then they joined the revolutionary armed forces and accompanied the Vietnamese volunteer army on the journey to liberate their Motherland. Their youthful and lively faces left a deep impression in me about a new generation who would master their country after the overthrow of the Pol Pot regime.

As we chatted, a soldier suddenly sat down by the piano and played a Cambodian folksong called Sai Kakeo and everyone started to sing along. It was really a special image that would last in my memory of the day of Phnom Penh liberation, and a precious detail in my first story about this newly liberated city.

After getting some information for writing, we and Nguyễn Chí Trung bid farewell with the soldiers, moved on our journey on Mounivong Boulevard and crossed the bridge to return to Việt Nam. It was noon. I still recalled Trung, with his big binoculars in hand, looking more like a commander than a writer. The four of us drove straight to Kandal and then Neak Loeung Ferry. At all costs, we must be in Hồ Chí Minh City as soon as possible. These would be the precious first reports on the liberation of Phnom Penh that our country looked for.

We could not travel fast due to bad roads and the long wait at Neak Loeung Ferry. Another reason was the car broke down. The jarring of the bumpy road had broken a battery wire, so the car would not start. Each time it stopped, we could only use our own strength to push it to start the engine. There were times we could seek help from some soldiers, but in most cases, we did it ourselves. We were constantly exhausted. The plain instant noodle soup could not help. And we had no time to ask for food at the nearby military units or families. On the way, we tried again to capture as many photos as possible because they could serve as valuable materials. I remembered that Cương was specifically interested in featuring Khmer female soldiers in Svay Rieng. Also here, he shot a special picture of a Cambodian girl on her way back to her home village. The girl was in her 16 or 17 years of age and had a beautiful face hiding discreetly under the scarf, sorrowful eyes and a mysterious smile. The picture was later named ‘The Bayon Smile’ and became famous. Those were so lively and persuasive.

The road was cut in many places and the car frequently broke down. Each time we saw a ditch in front, a cold wave rushed up our spine. When we crossed Mộc Bài border checkpoint and entered Tây Ninh, it was already dark. Without a battery, we did not have light either and had to run the car in darkness. Many other vehicles and people were taking the road then and it was quite dangerous, so we resorted to our electric torches. Cương and I sat on the side of the car and waved our torches to signal others on the road. But we must also save our torches too. As we turned on the torches, we also shouted out: "Keep distance, keep distance." When traffic was less busy, we just drove without light and tried to make out the direction to Hồ Chí Minh City.

It was quite late when we arrived in Hồ Chí Minh City. Trần Hữu Năng got out to see us. Immediately, the film rolls were sent to be developed and printed. I took the time to write down about what I saw in Phnom Penh in its first days of liberation. Năng took a look and made a quick edit before sending it all to the Front Command. Perhaps this was a quirk of the professional at that time. We could not transmit our pieces of news and photos on our own. The assistant unit of the Command would review and select with full consideration of all aspects. Late that night, the first photos were transmitted to Hà Nội. In the morning of January 9, all domestic newspapers and many foreign media agencies ran the photos of the liberation of Phnom Penh, Svay Rieng, Pray Veng and other photo stories about Cambodia under the name of SPK (mostly done by Lê Cương). We were quite glad about it. The next day, we received back our stories to send to headquarters, telling people about the atmosphere in liberated Cambodia and its capital.

Lê Cương, Thu and I were so happy. We had accomplished our mission well, adding our information and images about a historic military operation. Vietnamese and foreign media ran those articles and photos in their publications. A few days later, news and photos from other reporter groups were also sent back to the VNA headquarters, reflecting a panoramic view of the key directions on the battlefield. The Việt Nam News Agency again fulfilled its mission as a national media agency in these significant moments. Later, Lê Cưong told me that Deputy General Director Đỗ Phượng said: "You have met a clear goal for Việt Nam News Agency" when he inspected our news stories and photos and saw the soft caps of the Cambodian soldiers, not the hard hat of the Vietnamese army volunteers.

*Large excerpts from Vietnam News Agency veteran journalist Trần Mai Hưởng's book, Phóng viên chiến trường (War Correspondent), Vietnam News Agency Publisher, 2023

OVietnam