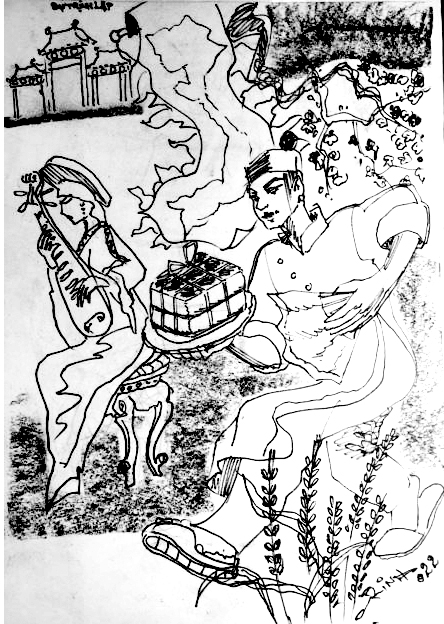

Illustration by Trịnh Lập

By Nguyễn Mỹ Hà

Bánh chưng -- the square glutinous rice cake that is part and parcel of the Tết (Lunar New Year) holiday -- is unlikely to ever be found on a list of popular international foods.

But for millions of Vietnamese living in the country or elsewhere in the world, bánh chưng is not merely a dish. Bánh chưng is the homeland, the happy childhood of hard manual work in the cutting cold winter. Bánh chưng is the original Vietnamese way of explaining the origin of the universe, and represents gratitude, the love of children who always find a way to show it to their parents regardless of circumstance.

This past week, during Tết, a Vietnamese writer, long-residing in Germany wrote of her perception of bánh chưng and enraged numerous Vietnamese, yours truly included. It is unnecessary to directly challenge what she wrote; I only want to say all the wonderful things I've lived and experienced with bánh chưng.

I love bánh chưng.

Legend has it that on the Spring celebration, King Hùng VI, one of the founding fathers of Việt Nam, challenged his sons to offer him the best food they could find, then he would pass his throne to the winner.

All the princes searched every corner of the world to fetch the most precious foods the forests and the seas could provide. The King's 18th son, Lang Liêu, despite being a prince, lived a modest life as his mother had died early.

As the day of offering became closer, Lang Liêu was anxious as he could not think of anything nor did he have the means to get any delicious foods. In his sleep, he was told by an elderly man that nothing in the world was more precious than rice. He then used the rice to make a pair of square cake and round bun representing the earth and sky, which impressed the King. The square cake was stuffed with pork, mung beans, spices and salt to represent the flora and fauna, and was wrapped in green leaves, symbolising the love of parents in all children.

Bánh chưng’s southern sister bánh tét (cylindrical rice cake) carries the same symbolic meaning. They both are a sign of Tết.

Bánh chưng is square and wrapped in wild canna leaves and bánh tét can be as long as half a metre and wrapped in banana leaves. They have meat in the centre, tucked in a bed of mung beans and are surrounded by glutinous rice all around, then are boiled for hours to get all the flavours mixed together.

They both have a salty original and a savoury variation. Bánh chưng can be cooked with a red sweet gourd (Momordica cochinchinensis) to make a sweet red square, and bánh tét can be made with five natural leave colours to make a beautiful round on the altar.

After a few days, they can be pan-fried to make a crispy hot version that can be taken as breakfast on cold winter mornings before school or work. For the best bánh chưng, I always add a drop or two of anchovy sauce from Phú Quốc, pickled shallots, as is the northern style, or fish sauce and dried turnips, as is the Huế and southern style. Sometimes I use pickled mustard greens, a style used throughout Việt Nam.

During the pandemic, for many, the first shipments of food for people in quarantine were small bánh chưng and bánh tét, where you could just unwrap the leaves and eat with your hands.

Children grow up having the tiny bánh chưng their parents make for them, usually cooked on top of a big pot and picked out early for kids to have before the rest of the family's cakes are ready.

I don't remember my first bite of bánh chưng, but I do remember the icy cold water I had to dip my hands in to wash the green leaves, the rice and mung beans. My neighbour friends now fondly share such memories; we remember how we all had to get the same ingredients ready for our mothers to make the cakes to cook overnight.

Then after 9 or 10 pm, when all the children were tired and had finished their baked sweet potatoes, the parents would stay up at night to add water and more wood and keep the fire alive for 10 or 12 straight hours until morning.

Bánh chưng is a symbol of childhood innocence, binding community ties, and above all, having the whole family doing something together. Back when food was scarce, we had to make about 20 to 30 pieces each Tết to give to our relatives. With so many bánh chưng available, children had Tết prolonged until the end of the first lunar month.

Back then storing food in a fridge was not an option, so my father put the cakes in layers of plastic and lowered them in our water tank underground to make them last. Every time we pulled them up from the water, we felt like we had caught a huge fish!

Now we can have bánh chưng all year round, and don't need so many to keep Tết alive, but making bánh chưng is still a fond time for the family. We no longer use the legendary wooden frame, and my child made one from her Lego blocks.

We invited my children’s friends over and made enough to give only one each. Though we do not have a wood-fired stove to cook our cakes, the electric stove manages the job of cooking a handful of pieces. The next morning, those cakes are much treasured.

On a culinary community Facebook page, there are countless posts of Vietnamese living abroad proudly showing off their fresh and carefully wrapped cakes, even though Tết is not a holiday for them and they still have to work full time.

"I had to build a tent in my garden to disburse the smoke from the makeshift wood-fired stove so that my neighbours would not be curious or call the police,” a man wrote. "When we make bánh chưng this Tết, I miss my mother and my home in Việt Nam." VNS

OVietnam