The picture shows the cover of 'Appetites and Aspirations in Vietnam' that is published by HCM City General Publishing House. Photo courtesy of HCM City General Publishing House

By Lương Thu Hương

Vietnamese cuisine has undergone significant changes over the centuries, shaped by various political and historical factors. In her book, Appetites and Aspirations in Vietnam, Erica J. Peters delves into the culinary history of Việt Nam, shedding light on how Vietnamese people used food and alcohol to establish their power and social position during the 19th century.

Appetites and Aspirations in Vietnam has been translated into Vietnamese and recently published in Việt Nam by HCM City General Publishing House.

Peters is co-founder and former director of the Culinary Historians of Northern California, the US. She had a BA from Harvard University and a PhD in history from the University of Chicago. She has written about various aspects of Vietnamese history and cuisine and presented at numerous conferences across the US and abroad.

Appetites and Aspirations in Vietnam is the result of 15 years of work by Peters, which began as a part of her doctoral thesis at the University of Chicago.

“What got me interested in Vietnamese history is that I spent a lot of time in France as a child, and I majored in French history in college. But when I went to graduate school in 1993, I became interested in studying French colonialism, and Việt Nam (one of France's colonies) was newly welcoming for visits from American researchers. In the spring of 1997 I first visited Hà Nội, and fell in love with the country, with the people, with the mist, and with the food. Most of my research was in archives and libraries (in Aix-en-Provence, Paris, and Hà Nội),” she told Việt Nam News.

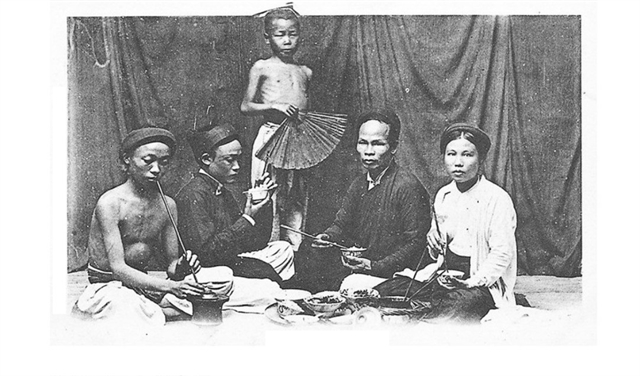

A family having a meal in northern Việt Nam. Photo courtesy of P.Dieulefils

Appetites and Aspirations in Vietnam starts with the spread of Vietnamese imperial control from north to south, marking the earliest efforts to create a common Vietnamese culture, as well as resistance to that cultural and culinary imperialism. Once the French conquered the country, new opportunities for culinary experimentation became possible, although such experiences were embraced more by the colonised than the colonisers.

This book discusses how colonialism changed the taste of Vietnamese fish sauce and rice liquor and shows that state intervention made those products into tangible icons of a unified Vietnamese cuisine, under attack by the French.

Vietnamese villagers began to see the power they could bring to bear on the state by mobilising around such controversies in everyday life. The rising new urban classes at the turn of the twentieth century also discovered new perspectives on food and drink, delighting in unfamiliar snacks or giving elaborate multicultural banquets as a form of conspicuous consumption. New tastes prompted people to reconsider their preferences and their position in the changing modern world.

“The aspect I found most interesting was reading subtle suggestions that the Vietnamese were more civilised than the French (around the end of the 19th century) because most of the French never managed to learn how to use chopsticks,” Peters said.

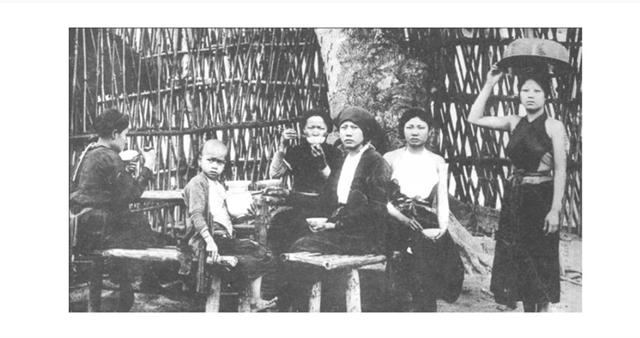

Northern wơmen having a meal. Photo courtesy of P.Dieulefils

A part of the book examines the influence of Chinese culture and cuisine on Vietnamese cuisine through the settlement of migrant Chinese in the country. In fact, during the 1870s and 1880s, it was a commonly held belief in southern Việt Nam that male Chinese chefs were extremely skilled in the kitchen.

In addition to the close encounters regarding cuisine and ethnicity, the book also mentions food clashes that demonstrate the high spirit of the Vietnamese beyond the realm of food and drink.

"In August 1919, a Chinese café owner in the Saigon suburbs raised the price of a cup of coffee from two cents to three cents, sparking a crisis. Vietnamese journalists stirred up public support with the goal of limiting Chinese domination over the economic life of the South," Peters writes in her book.

The book also analyses the strong resistance by the silent majority of Vietnamese residents to the invasion and coercion of French cuisine. This resistance was particularly evident in the context of traditional wine being classified as illegal liquor by the colonial authorities in order to force people to use state-produced alcohol, which was simply a tax-collecting policy.

Many clashes between clandestine home brew and state-produced alcohol took place, essentially confrontations between the Vietnamese and the French in the battle for drinks. Towards the end of 1911, with a record number of Vietnamese villagers drinking untaxed liquor instead of official products, the French government intensified its efforts to address the issue.

"In 1912, Sarraut was forced to 'reduce the tax by a few centimes and force the Fontaine brothers to cut their excessive profits from their ten-year monopoly [...] improve the quality of rice wine and reduce its purity to bring the product closer to the taste that Vietnamese consumers demanded,'" Peters notes.

As Western cultural influences poured into Việt Nam during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it was inevitable that cuisine would also undergo a process of fusion, contributing to the creation of a diverse range of flavours. The book identifies canned goods, bread, cow's milk, and sandwiches, among others, as examples of Western influences that have enriched Vietnamese cuisine.

“Wandering the streets of Hà Nội, one can now find phở shops near bakeries selling bánh mỳ (warm, crusty baguettes, which make for excellent sandwiches) and market vendors offering freshly sliced and salted pineapple next to cafés where Vietnamese and tourists enjoy rich cups of coffee. Two hundred years ago, none of those delights were there. A hundred years ago, they had all just arrived.” Peters writes.

"The French colonisers who conquered Việt Nam in the second half of the 19th century are long gone, but certain culinary contributions remain, alongside contemporaneous influences from other people: Chinese, Indians, Khmer, Malay and others.

“What I hope readers will take away is that what we eat is never fixed in time. Every day we can choose to eat something new, to learn about a new culture, or to share food with someone we're interested in, who likes some food we're not yet familiar with. Every day is an opportunity for a new flavour, or an old favourite, and we can learn a lot about ourselves and each other by talking about the foods we love.” VNS

A market in Northern Việt Nam . File photo

|

Crossing culinary cultures

“What happened when French and Vietnamese encountered each other's cuisines? Breaking new ground by examining colonial culinary history, Peters challenges the old saw that we are what we eat, suggesting instead that we eat what we want to be. By seeing the Vietnamese as well as the French as colonialists, by looking at the alcohol monopoly and imported foods, by exploring the role of the Chinese, and by teasing out cross-influences between all these cuisines, Peters illuminates the complexity and instability of a hundred years of culinary change in Vietnam. A refreshingly original contribution to culinary studies,” Rachel Laudan, food historian.

|

OVietnam